“Flying an approach is not difficult. A smooth approach takes practice. To execute an effortless approach, mastering the trim wheel is key.”

That is what I concluded

I recently found this journal I wrote back in the day I did my Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) training. I miss those days flying in the US. Hope you like it and share your thoughts with me!

Taking off is easy. Landing is hard.

Majority of the IFR training is to prepare me for the approach. Taking off in Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC) for small training aircraft is easy. Even if I couldn’t see where I am flying, as soon as I hit the rotation speed, back pressure on the yoke, off I go knowing I won’t hit anything. Just as long as I maintain the correct heading and I will be cleared of all structures within minutes. But landing is a different story. Although the whole approach is done within a few minutes, it always feels way longer than that. Not sure why, but my number one worry when flying an approach was to crash into the control tower. Come to think about it now, I was so silly.

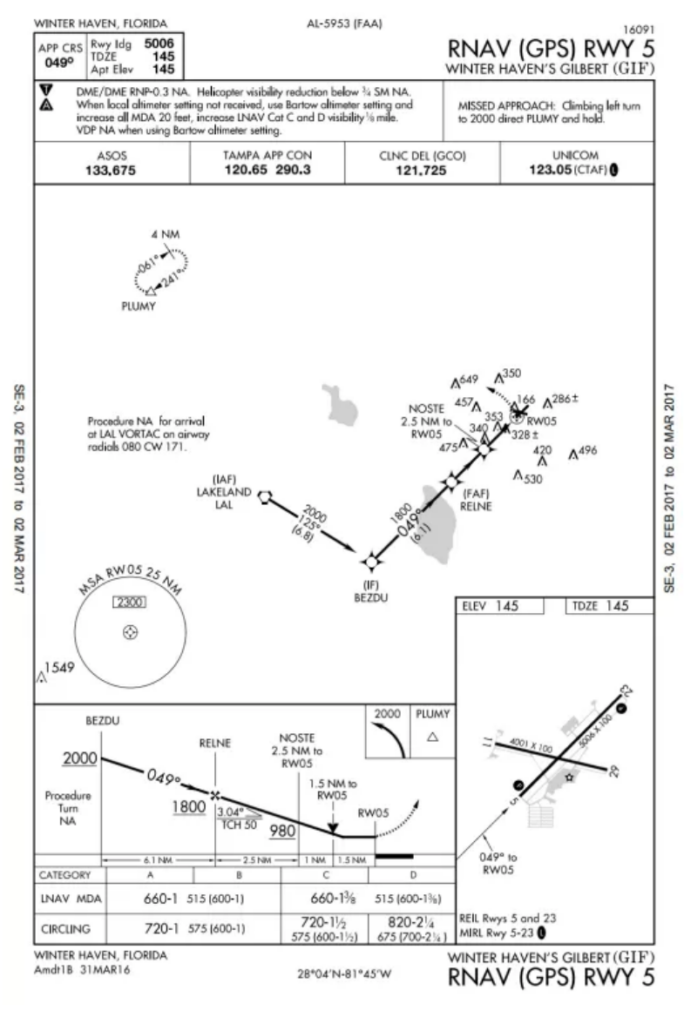

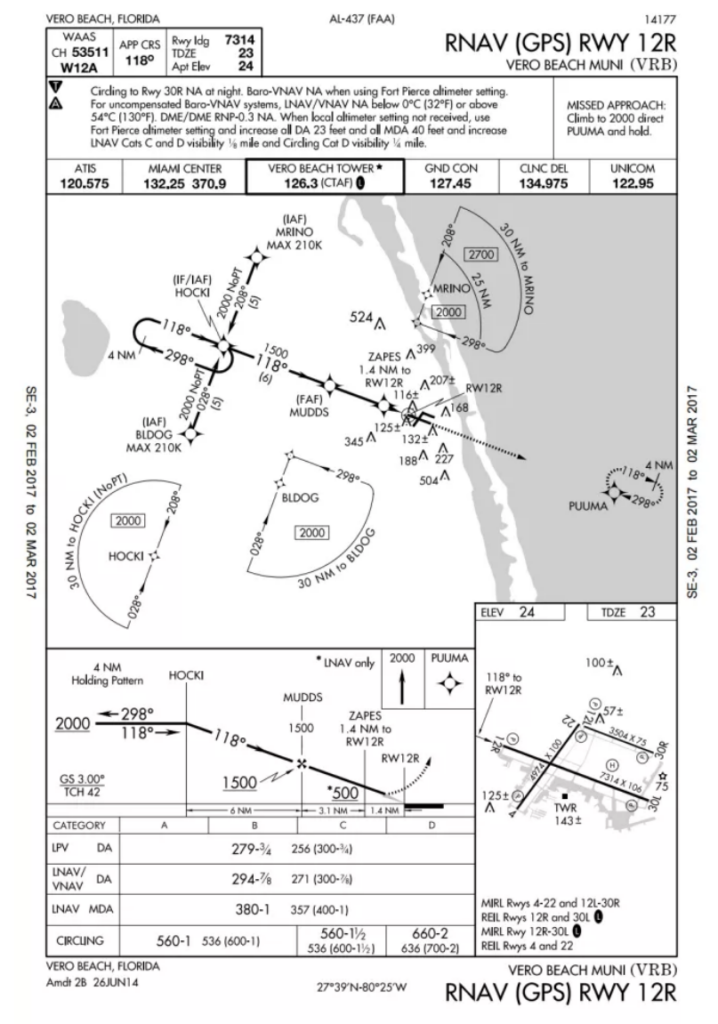

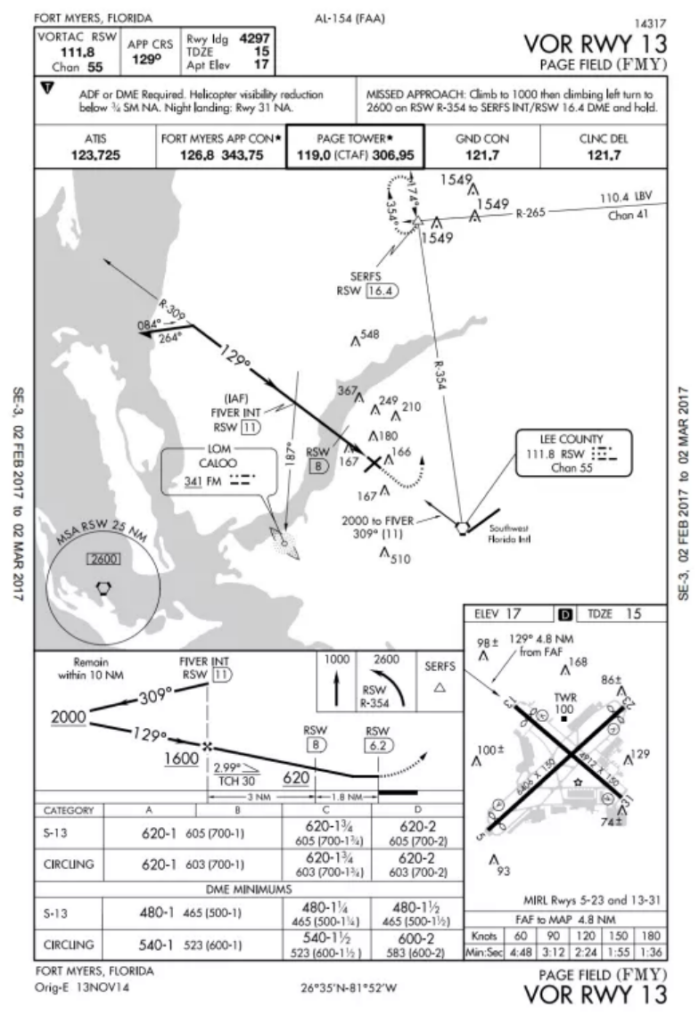

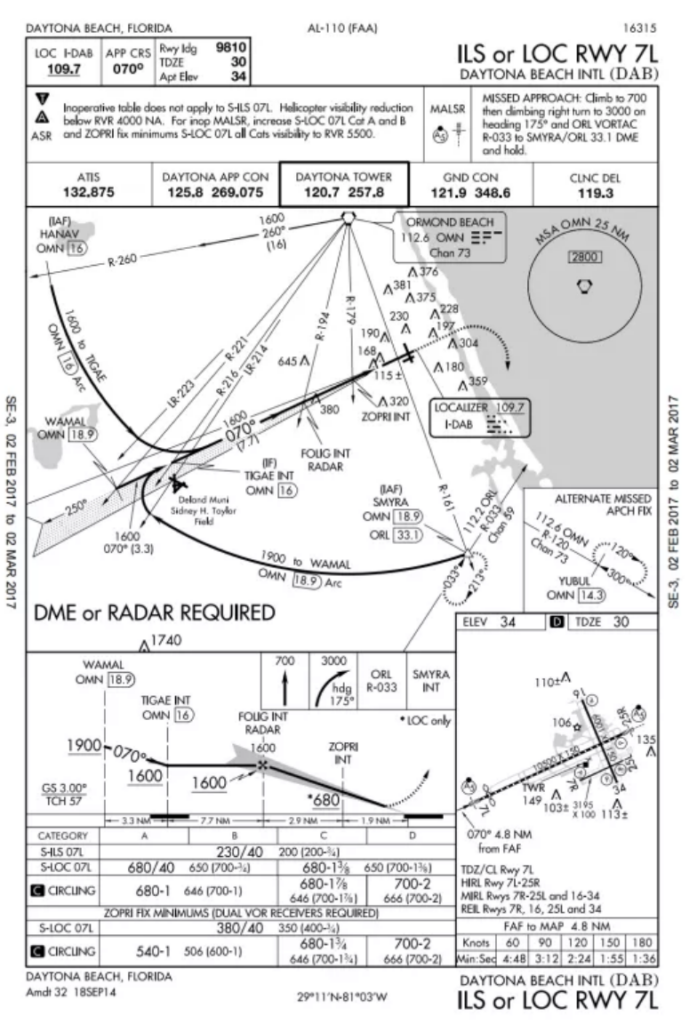

Approach Plate

Approach plates are beautiful things. I always thought they would be nice posters if I want to decorate my room with an aviation theme. Though they are nice to look at, using them are less nice. Before every approach, it is part of the landing checklist to brief the approach plates. The first few times I brief the approach plates, my airplane was all over the place. Altitude change (more than 100 feet) and heading change (more than 10 degrees) happened in an instant. I didn’t even feel the change. My flying was so bad that it was illegal!

Why did that happen? I was too slow. Surely, whoever have an instrument rating would understand the amount of workload I had. I need to fly the airplane, comply with ATC’s instructions, upload the approach into the G1000 and brief the approach plate before executing the approach. The pressure I had was so immense that it was fun!

Autopilot was not allowed. Which was a good training for me.

It took me quite some time to effectively manage my workload. Soon, I was able to fly three approaches, one after the other without much problem. The key is to prepare everything in advance while I can. There is no time to admire the scenery or chat with my instructor. Focus on the task ahead is key. Any mistake that just happened must be corrected quickly and ignored immediately. There is no time to ponder on the mistake that I just made.

Below are some of the approaches I have flown.

Winter Haven

Vero Beach

Page Field

Daytona Beach International

Runway in Sight

“Runway in sight” that was the sign to take off the hood. Whenever the hood was off, there will be a moment of shock to see how near the runway was. My approach speed was 90 knots. Now, I need to get it down to below 70 knots (depending on wind speeds) to land the airplane. What I usually do in my VFR days was to hold the pitch to bleed off the airspeed. That was an effective way to kill airspeed but doing that in an instrument approach was a big NO NO.

Just imagine, when I hold the pitch to bleed off airspeed, what happens? I am not only reducing the rate of descent, at times, I may even go into a slight climb. This is a bad idea because I may end up in IMC again. In the worst case, I might need to do a miss approach. That was what I was told because all my approaches up till this point were done in Visual Meteorological Condition (VMC) under the hood.

The correct way to do it is to reduce power to bleed off airspeed and remain on the glide slope (if there is a glide slope). Slow down to the desired speed, add flaps and a smooth touch down.

To be honest, throughout my IFR training, I have never done an approach in IMC. I did fly through clouds during my cross country but not an approach with low visibility.

My first proper IMC approach came after I got my rating, ying with a full load and without an instructor. A story for another day.